ウイリアム・H・ユーカース(William H. Ukers)と100年のオール・アバウト・コーヒー(All About Coffee)

コーヒーの真実(The Truth about Coffee)

1901年、当時27歳だったウイリアム・H・ユーカース(William H. Ukers, 1873 - 1945)は、1878年にニューヨークのコーヒー焙煎業者ジャベス・バーンズ(Jabez Burns)が創刊した社内報『ザ・スパイス・ミル(The Spice Mill)』の編集に携わっていた。成長に伴い、彼は業界誌に発展させることを上司に提案したが、却下され、あっけなく辞めてしまった。

伝えられる話によれば、その日、ユーカースは『ティー&コーヒー・トレード・ジャーナル(Tea & Coffee Trade Journal)』 を創刊したそうである。 彼は生涯をこの雑誌と出版社に捧げ、最新のルポルタージュと歴史的・科学的分析を融合させた出版活動を続けた。『ザ・スパイス・ミル』が食料品ビジネスに重点を置いていたのとは対照的に、『ティー&コーヒー・トレード・ジャーナル』は国際貿易により重点を置いていた。

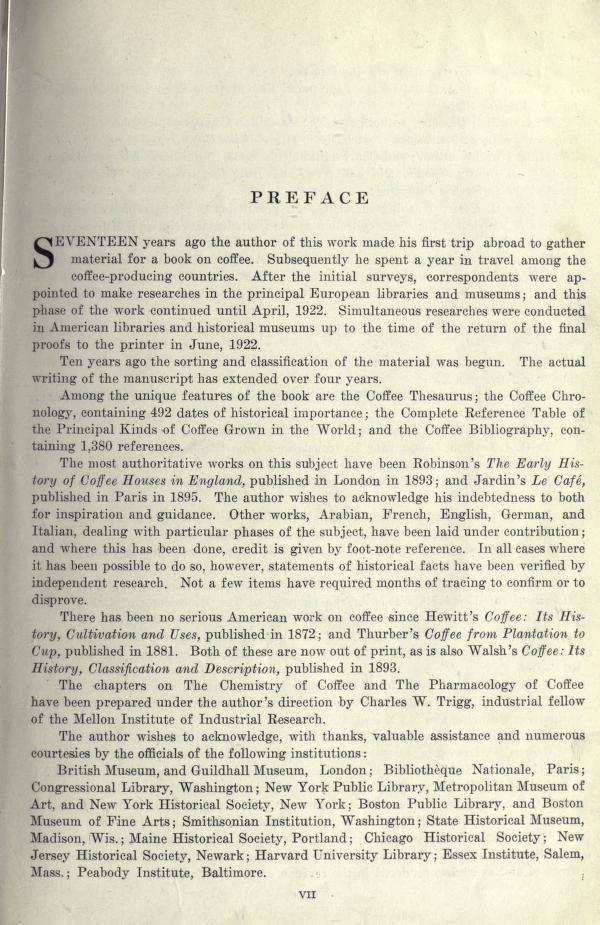

ウィリアム・H・ユーカースは、30歳そこそこで、1905年から1年間、旅をして資料を集め、本の制作に取りかかった。ニューヨークに帰ると、近くの図書館や博物館を探し回った。自分で行けないところは助手を派遣し、ヨーロッパ、特にロンドンとアムステルダムのコレクションを掘り起こすよう任命した。7年間の調査の後、ユーカースは、次々と送られてくる収集資料の整理を始めた。6年後、彼は執筆活動を開始した。執筆するにつれ、新たな疑問が浮かび、それに答えようと数カ月を費やした。4年の執筆期間を経て、50歳近くになったユーカースは、1922年の春に最後の逃げ去る事実を突き止めた。6月、『オール・アバウト・・コーヒー』は印刷所に持ち込まれた。

この本は、コーヒー業界の2つの業界紙のうちの1つであり、月刊機関誌も発行していた『ティー・アンド・コーヒー・トレード・ジャーナル・カンパニー』から出版された。もう1つは、1878年にニューヨークのコーヒー焙煎業者ジャベス・バーンズが設立した『ザ・スパイス・ミル』である。ユーカースはザ・スパイス・ミルの記者としてキャリアをスタートさせ、1902年に編集長に昇進した。1904年に退社し、『ティー・アンド・コーヒー・トレード・ジャーナル 』を引き継いだ。『ティー・アンド・コーヒー・トレード・ジャーナル』は、『ザ・スパイス・ミル』が食料品ビジネスに重点を置いていたのとは対照的に、国際貿易により重点を置いていた。毎月、コーヒー本の執筆と並行して、同じテーマの雑誌を執筆、編集、出版していたのである。

業界誌はともかく、コーヒーはアメリカ生活におけるその重要性に見合うだけの文学作品の対象にはなっていなかったのである。ユーカースは序文で、『オール・アバウト・・コーヒー』はアメリカで40年以上ぶりに出版された本格的なコーヒーに関する本であり、1881年のフランシス・ビーティ・サーバーの『フロム・プランテーション・トゥー・カップ』以来、そしてそれ以前は1872年のロバート・ヒューイット・ジュニア『コーヒー:その歴史、栽培、使用法』以来である、と述べている。ユーカースは寛大だった。実際、彼の本には前例がない。大判2段組の小さな活字に、カラー図版17点、モノクロ図版500点、肖像画100点、地図・図表30点と、800ページ近いボリュームであった。中でも、歴史的に重要な492の年代を記した「コーヒー年表」、「世界で栽培されているコーヒーの主要な種類の完全参考表」、索引の前の最後のセクションで、3段組28ページの1,380の文献を網羅した「コーヒー文献目録」は、ユーカースの自慢の一品であった。

ウイリアム・H・ユーカースは、コーヒーについて知り尽くしていた。しかし、コーヒーについて最も重要なことでありながら、知ることができないことがあった。彼の本の真ん中には、チャールズ・W・トリッグの署名入りの2つの章があった。「コーヒー豆の化学的性質」と「コーヒー飲料の薬理学的性質」について書くようにと、ユーカースはトリッグに依頼した。これらのテーマは複雑で難しく、しかも利害関係があるため、専門家の権威が必要だったのである。

William H. Ukers, not much over thirty, started working on his book in 1905, traveling and gathering material for a year. After he returned home to New York, he scoured nearby libraries and museums. Wherever he couldn’t go himself, he sent auxiliaries, appointing research assistants to mine collections in Europe, especially in London and Amsterdam. After seven years of research, Ukers began to organize the material he had collected, even as it continued to come in. Six years later, he began writing. As he wrote, new questions came up that he spent months trying to answer. After four years of writing, Ukers, now almost fifty, tracked down his last fugitive fact in the spring of 1922. In June, All About Coffee went to the printer.

The book was published by the Tea and Coffee Trade Journal Company, which also published a monthly bulletin, one of two trade papers for the coffee industry. The other was The Spice Mill, founded by New York coffee roaster Jabez Burns in 1878. Ukers had started his career as a reporter at The Spice Mill, and he was promoted to editor in 1902. He left in 1904 to take over the Tea and Coffee Trade Journal, which, in contrast to The Spice Mill’s emphasis on the grocery business, focused more on international trade. Every month, as he worked on his coffee book, Ukers was also writing, editing, and publishing a magazine on the same subject.

Trade journals aside, coffee had not been the subject of literary output equal to its importance in American life. In his foreword Ukers noted that All About Coffee was the first serious work on the topic published in the United States in more than four decades: the first since Francis Beatty Thurber’s From Plantation to Cup in 1881, and, before that, Robert Hewitt Jr.’s 1872 Coffee: Its History, Cultivation, and Uses. Ukers was being generous. In fact his book had no precedent. It spanned nearly 800 large‑format, two‑column pages of small type, plus 17 color illustrations, 500 black‑and‑white illustrations, 100 portraits, and 30 maps, charts, and diagrams. Among the features Ukers was most proud of were the “Coffee Chronology,” marking 492 dates of historical importance; the “Complete Reference Table of the Principal Kinds of Coffee Grown in the World”; and the “Coffee Bibliography,” encompassing 1,380 references, the last section of the book before the index, itself 28 three‑column pages.

William H. Ukers knew everything there was to know about coffee, but there were also some things about coffee—some of the most important things—that seemed unknowable. In the middle of his book were two chapters under the byline of Charles W. Trigg. Ukers had commissioned Trigg to write about “The Chemistry of the Coffee Bean” and “The Pharmacology of the Coffee Drink.” The complexity and difficulty of these subjects, and their stakes, demanded the authority of a specialist.

Augustine Sedgewick(2020)"Coffeeland: A History" 16. The Truth about Coffee

数十年にわたってコーヒーの研究を続けたユーカースにとって知りえない謎として残ったのが、「コーヒー豆の化学的性質」と「コーヒー飲料の薬理学的性質」であった。彼はこのテーマについては、化学者のチャールズ・W・トリッグ(Charles W. Trigg)に執筆を依頼した。

トリッグは、化学技術者であった。本業は彼はおそらくこの国のインスタントコーヒーの第一人者であった。1901年のバッファロー万国博覧会で、日本の水出し茶をモデルにした水出しコーヒーが公開され、「レッド・イー」という威嚇的な商品名で広く小売されることになった。鉄道会社、製糖会社、シンガーミシン会社など、アメリカ経済においてコーヒーがいかに重要な役割を担っているかを示す利害関係者の集まりであった。トリッグは、ピッツバーグのメロン研究所で学術研究を行っていた。『オール・アバウト・コーヒー』が出版された1922年、彼はデトロイトのキング・コーヒー・プロダクツで主任化学者の職にあり、「ミニッツ・コーヒー」というインスタントコーヒーと「コーヒー・ペップ」というコーヒー・ベースの清涼飲料という、アメリカの工業都市で明らかに価値のある2つの製品の開発に取り組んでいたのである。

トリッグが『オール・アバウト・コーヒー』に寄稿した章には、その産業志向が表れている。「コーヒー・ビジネスの広大な範囲と、平均的な人間の日常生活との密接な関係を考えると、コーヒーの化学成分や生理作用に関する正確な知識は比較的少ないことに、驚きを禁じ得ない」と書いている。彼は「驚き」を肯定的な意味で使ってはいない。「コーヒーが 『不老不死の薬』であるとか、あるいは毒であるといった趣旨の文献を選ぶことは可能である。これは、消費者の間に正しい知識を普及させるために計算されたものではなく、嘆かわしい状態である」とトリッグは続けた。つまり、何か他のことを促進するために作られたものだということである。

この国で最も声高に反コーヒーを唱えたのは、穀物王でモラリスト、神経衰弱にかかったC・W・ポストであることは間違いない。神経衰弱は、19世紀末のアメリカでは一般的な診断名で、症状としては、ベッドで休養するほど衰弱した状態になる。ポストも1890年に悪化し、30代半ばで運を使い果たした。30代半ばの運の悪い時だった。治療法を求めて、ミシガン州バトルクリークにあるジョン・ハーベイ・ケロッグの療養所を訪れた。ケロッグは、紅茶と並んでコーヒーを「アメリカ国民の健康に対する重大な脅威」と位置づけ、熱心に反対していた。アメリカで神経衰弱が流行した背景には、国そのものが弱くなっているのではないかという大きな不安があった。ケロッグは、コーヒーがアメリカ人の活力を吸い取り、早老に導く中毒であると考えた。ケロッグの療養所では、朝食に特許を取得したシリアルと、パンの耳、ふすま、糖蜜から作った「キャラメルコーヒー」と呼ばれるものを出していた。

多くの神経衰弱患者にとって、療養所は太陽の光を浴びるための場所であった。これに加えて、ポストはケロッグのアイデアを取り入れた。1892年、ポストはバトルクリークに「ラ・ヴィータ・イン」という療養所をオープンさせるまでに回復した。1895年には、「ポスタム」と名付けたコーヒーの代用品も作った。間もなく、彼はこのミックスを食料品店に売り込み、店から店へと携帯用ストーブを持ち歩き、立ち寄るたびにポットでコーヒーを淹れるようになった。ポスタムコーヒーのレシピは、20分ほどで完成するものだった。「よく淹れると、ポスタムはコーヒーのような茶色で、味はジャワのマイルドなものによく似ている」と、ポスタムは主張した。さらに重要なのは、彼の健康に対する主張である。ポスト社は、「ポスタムは、赤い血液を作る」と言い、ポスタムを大衆向けに販売するために、創業資金を調達した。

ポストは、焙煎した穀物と糖蜜のブレンドを売り込むために、ケロッグ同様、コーヒーを毒物として扱った。広告では、コーヒーを飲む人に「コーヒー心臓」「コーヒー神経痛」「脳障害」「失明」「潰瘍」「脳組織の崩壊」「消化不良」「労働時間の短縮」「低エネルギー」「貧困」「無名」「麻痺」といった警告を発した。1902年、コーヒーの常飲者であったポストは、100万ドルを手にした。1905年、ポストの娘マージョリーが豪華な結婚式を挙げた後、ウィリアム・H・ユーカースは『ティー・アンド・コーヒー・トレード・ジャーナル』に、結婚式の費用を負担した「アメリカ国民のだまされやすさ」を嘆く厳しい論説を書いた。

ウイリアム・H・ユーカースは、チャールズ・トリッグに「コーヒーについて真実を語れ」と命じ、ポストを科学的に説き伏せることにした。トリッグは『オール・アバウト・コーヒー』の中で、「コーヒー抽出物の摂取は、常に刺激を与える証拠となる」と書いている。「神経系に作用して、精神活動を高め、知覚の力を速め、思考をより正確かつ明瞭にし、知的作業を容易にするが、その後に明らかに落ち込むことはない。筋肉はより活発に収縮し、作業能力を高めるが、二次的な反応として作業能力の低下につながることはない。」 不眠症、神経衰弱、痛風、中毒など、コーヒーにまつわる罪状を列挙し、ことごとく反論した。コーヒーが体に悪いと思い込んでいる人たちがいることは、彼も認めており、その中には、「非常に神経質な」C・W・ポストのような神経症のアメリカ人が1〜3%いるという。「だから」、トリッグは、「もし、自分が異常な少数派に属していることに個人的に満足しており、コーヒーが自分を傷つけるという誤った推論を議論していない場合は、コーヒーの消費を減らすか、放っておけばよい」と理性的に結論づけたのである。

Trigg was a chemical engineer by training. By trade he was probably the country’s leading authority on instant coffee. Soluble coffee manufactured on the model of Japanese soluble tea had made its public debut at the Buffalo Pan‑American Exposition in 1901, and the first widely available retail product was known by the fairly menacing brand name Red E. Among its backers were executives from railroads, sugar refining, and the Singer sewing machine company, a consortium of interests that illustrates the role coffee drinking had come to occupy in the American economy. Trigg had done his academic research at the Mellon Institute, in Pittsburgh. When All About Coffee was published in 1922, he held the position of chief chemist at King Coffee Products in Detroit, where he was working on two products with clear value in America’s industrial cities: an instant brew called “Minute Coffee,” and a line of coffee‑based soft drinks called “Coffee Pep.”

The industrial orientation of Trigg’s work came through in the chapters he contributed to All About Coffee. “When the vast extent of the coffee business is considered,” he wrote, “together with the intimate connection which coffee has with the daily life of the average human, the relatively small amount of accurate knowledge which we possess regarding the chemical constituents and the physiological action of coffee is productive of amazement.” He did not use “amazement” in a positive sense. “It is possible to select statements from literature to the effect either that coffee is an ‘elixir of life,’ or even a poison. This is a deplorable state of affairs,” Trigg went on, “not calculated to promote the dissemination of accurate knowledge among the consuming public.” The implication was that it was calculated to promote something else.

Arguably the loudest anti‑coffee voice in the country was C. W. Post, cereal mogul, moralist, recovered neurasthenic. Neurasthenia was a common diagnosis in late‑19th‑century America, a condition indicated by symptomatic exhaustion that left its sufferers weakened to the point of bed rest. Post’s case had gotten bad in 1890, when he was in his mid‑thirties and down on his luck. In search of a cure, he went to John Harvey Kellogg’s sanitarium in Battle Creek, Michigan. Kellogg was a dedicated opponent of coffee, which he identified, along with tea, as “a grave menace to the health of the American people.” The larger fear behind the American epidemic of neurasthenia was that the nation itself was getting weaker. Kellogg considered coffee an addiction that was sucking Americans’ vitality right out of them, leading to premature old age. For breakfast Kellogg’s sanitarium served his own patented cereal blends and what he called Caramel Coffee, made from bread crusts, bran, and molasses.

For most neurasthenics, sanitariums were places for soaking up the healing properties of the sun. In addition to this, Post took Kellogg’s ideas. By 1892, Post was well enough to open a sanitarium of his own in Battle Creek, which he called La Vita Inn. To provision it, he began to make his own strengthening foods, including, in 1895, his own coffee substitute, which he called Postum. Soon he began selling the mix to grocers, toting a portable stove from store to store and brewing up a pot at each stop. The recipe called for twenty minutes of brewing, plenty of time for a pitch. “When well brewed,” Post claimed, “Postum has the seal brown color of coffee and a flavor very like the milder brands of Java.” Even more important were his health claims. “It makes red blood,” Post promised as he raised start‑up funds to bring Postum to the mass market.

To promote his blend of roasted grains and molasses, Post, like Kellogg before him, cast coffee as a poison. Advertisements warned coffee drinkers of “coffee heart,” “coffee neuralgia,” “brain fag,” blindness, ulcers, disintegration of brain tissues, indigestion, reduced work time, low energy, poverty, obscurity, and paralysis. By 1902, Post—a habitual coffee drinker himself—had made a million dollars. After Post’s daughter, Marjorie, married in lavish style in 1905, William H. Ukers wrote a scathing editorial in the Tea and Coffee Trade Journal bemoaning the “gullibility of the American public,” who had after all paid for the wedding.

“Tell the truth about coffee”—that was the assignment William H. Ukers gave Charles Trigg, and it meant putting Post in his place with science. “The ingestion of coffee infusion is always followed by evidences of stimulation,” Trigg wrote in All About Coffee. “It acts upon the nervous system . . . increasing mental activity and quickening the power of perception, thus making the thoughts more precise and clear, and intellectual work easier without any evident subsequent depression. The muscles are caused to contract more vigorously, increasing their working power without there being any secondary reaction leading to a diminished capacity for work.” Having noted these benefits, Trigg proceeded down a list of the charges against coffee, refuting every one: insomnia, enervation, gout, addiction. There were, he acknowledged, certain people who had tricked themselves into believing that coffee was bad for them, including the 1 to 3 percent of Americans who were “very nervous”—neurasthenic, like C. W. Post. “So,” Trigg concluded, reasonably, “if one is personally satisfied that he belongs to the abnormal minority, and has not been argued by fallacious reasoning into his belief that coffee injures him, he should either reduce his consumption of coffee or let it alone.”

Augustine Sedgewick(2020)"Coffeeland: A History" 16. The Truth about Coffee

2022年6月17日の今日は、『オール・アバウト・コーヒー(All About Coffee)』の初版が出版された1922年6月17日からちょうど100年である。しかしいまだに、「コーヒーはその重要性に見合うだけの文学作品の対象にはなって」いないし、「コーヒーが 『不老不死の薬』であるとか、あるいは毒であるといった趣旨の文献を選ぶことは可能」であることにも変わりない。

当時、いまだ解明されていなかったコーヒーの科学的側面は、謎めいた宗教的迷信や医学的偏見を生み出し、「他の何かを促進するために作られたもの」として政治的・経済的に利用することを可能にした。そのため、相容れない議論や主張に対して「コーヒーの真実」を語ることは、「コーヒーの科学」を語ることと同義だったのである。

しかし、トリッグが解決できなかったコーヒー科学の核心にある曖昧な点がある。ポストの反論として、彼はコーヒーを飲むと「仕事の能力が上がる」と結論づけた複数の実験結果を引用した。しかし、その効果は明らかであっても、その原因は曖昧なままだった。なぜコーヒーを飲むと労働能力が高まるのか、既存の実験では明確に立証されていなかったのだ。トリッグは、「コーヒー飲用が人体に及ぼす影響」について、これまで言われてきた「嘆かわしい」矛盾を明らかにしたかったが、コーヒーと人体、エネルギー、仕事との関係を正確に説明することができなかったのである。しかし、ウイリアム・H・ユーカースは、科学的な疑問のほとんどをトリッグに譲り、徹底的な研究の過程で、自分にとって正しいと思われる説明を導き出したのである。コーヒーは、「人間のエネルギーと効率の副産物」であると、ユーカースは序文で書いている。それは「人間の機械にとって最もありがたい潤滑油」であった。

今日、カフェインが特別なのは、それがあまりにありふれたものだからである。アメリカ人の大部分(おそらく80パーセント)が毎日使っているカフェインは、「どう考えても、世界で最も人気のある麻薬であり、世界中で抵抗と不評を克服して、ほとんどどこでも自由に手に入り、規制もなく、許可なく販売され、タブレットやカプセルの形で市販され、子供向けの飲料にさえ添加されている唯一の常習性精神活性物質」である。しかし、2世紀前、カフェインが発見されたとき、カフェインはありふれたものではなかった。むしろ、カフェインは自然の崇高な複雑さを映し出す窓だったのだ。

ナポレオンのヨーロッパで最も有名な知性であるヨハン・ヴォルフガング・フォン・ゲーテは、その人生の終わり頃、世界を結びつけている目に見えないつながりを心の中で見ることができた。彼はデカルトの心と体の分離を否定した。ゲーテは、デカルトの心と体の分離を否定し、ニュートンの宇宙を独立したパーツに分割し、それぞれを分析するという考えを否定した。ゲーテは、自分が思い描く「全体性」を証明するもの、つまり「各部分がどのように作用しているか」を示す具体的な例を求めていたのだ。彼は友人との会話でこう言った。「自然界では、孤立したものを見ることはなく、すべてが、その前、その横、その下、その上にある他の何かと関連している」。彼の考え方は、科学が目指す方向を指し示していた。ドイツの医師ヘルマン・フォン・ヘルムホルツは、1847年にエネルギー保存説を発表したが、ゲーテはこの説を先取りしていたと考えている。

1819年、かつてコーヒーをこよなく愛した70歳のゲーテは、「非常に有望だ」と思っていた若い知人、つまりフリードリッブ・ルンゲという医師に、モカ港でとれたコーヒー豆を1箱渡し、その中に何があるのか、どう働き、何をし、広い世界とどんな目に見えないつながりを持っているのかを解明するように命じた。当時、コーヒーが人体に及ぼす影響の原因や性質については、ほとんど解明されていなかった。体液系に基づく何世紀もの医学思想を覆し、ルイ・パスツールなど、近代医学はまだ生まれてもいない時代であった。

ルンゲはゲーテの挑戦を受けた。数ヶ月の研究の後、彼はアルカロイドという植物の基質を単離し、ドイツ語の「コーヒー」にラテン語の「〜の性質を帯びて」を意味する接尾語「ine」を加えて「カフェイン」と名づけた。この発見の条件は、しばらくの間、厳格に守られた。1827年に茶葉からアルカロイドが単離された時、「テイン」と呼ばれた。カフェインと化学的に同一であることが判明した後も、カフェインは植物の中で、ある種の有害生物に対する殺虫剤として、ある種の有用生物に対する興奮剤として進化してきたと考えられていたのである。ルンゲは商業化学で成功を収め、そのマイルストーンの1つは、コールタールから青色染料を合成することに先駆的に取り組み、繊維メーカーがその副産物で布を着色できるようにし、エルサルバドルなど世界各地の藍生産者に他の換金作物への転換を促したことは画期的な出来事だった。

コーヒーの化学分析が、その効果に新たな光を当てた。コーヒーには、3つの「活性原理」、つまり「原因」があることがわかったのだ。カフェインのほか、アロマとフレーバーのもととなる精油のカフェオン、これもまたフレーバーに寄与する必須酸のカフェ酸である。この発見は、コーヒーの固定的な定義を確立し、代替品や純度への関心が高まっていた食品ビジネスにとって重要な意味を持つことになった。あるコーヒー商人は、「これらの要素はそれぞれ独自の美点や力を持ち、コーヒーがもたらす一般的な効果に一役買っている」と書いている。この3つの「活性」成分が一緒になって、コーヒーに商材としての「個性」を与えているのだ。この3つの要素がないものは、コーヒーではないのだ。

しかし、この3つの「活性原理」を中心に「コーヒー」の定義が形作られていっても、人体への作用や効果については、憶測や意見の相違があるままだった。カフェインはいったい何に、どのように作用するのだろうか。「コーヒーは横隔膜と太陽神経叢に作用し、あらゆる分析を免れた計り知れない発散によって脳に広がる」と、オノレ・ド・バルザックは1839年に書いている。「しかし、この物質が放出する電気を伝導するのは、神経系の液体であり、この物質が我々の体内で見つけたり刺激したりするのだと推測できる」。長い間、この科学は確定的であると同時に曖昧なままであった。ルンゲの発見から一世紀以上たった今、ある研究者は、コーヒーに関する科学論文を「化学者、生理学者、心理学者、栄養士、医師、食品検査官など、食品や食物の準備、分析、効果にまったく関係のないあらゆる種類の科学者」から700編以上数えたという。そのうちの3分の1にあたる232人が、コーヒーの身体への影響に着目していた。その結果、チャールズ・W・トリッグが嘆いたように、互いに激しく対立することがしばしばであった。

W・O・アトウォーターの熱量計では、人体の動きがかつてないほど正確に測定されたが、コーヒーの効果は不明であった。ドイツで行われた労働者の食生活の研究では、コーヒーの労働力への寄与を説明しようとしたが、アトウォーターはコーヒーと紅茶を他の食品と区別し、カフェインの体内作用をコーヒー1杯の脂肪(精油)に由来するわずかなカロリーから切り離したのである。アトウォーターは、「普通の人、たとえば機械工や日雇い労働者で、かなりの量の手作業をしている人が1日生活するのに必要な食べ物」を研究する中で、多くの被験者がコーヒーを常飲していることを認めたが、「計算を簡単にする」ために、最終的にエネルギー計算から除外してしまった。

「お茶やコーヒーは、私たちが使う意味での食品ではない」-「体内に取り込まれると、組織を形成するか、エネルギーを生み出すか、あるいはその両方に役立つ物質」-と彼は書いています。彼は、コーヒーが身体、特に呼吸と代謝に何か作用していることは知っていた。「活力を与える効果があり、時には消化を助けることもある」。アトウォーターは、「おそらく、ほとんどの人はお茶やコーヒーを飲まない方がよいだろう」と結論づけ、研究室でその原則を守っていた。W・スミスが熱量計の中で、自分の体が従わずにはいられない法則を理解するために、ドイツの物理学の論文を読んで苦労している間、彼が飲むのは水と牛乳だけであった。

アトウォーターがコーヒーに対して抱いていた不安は、金ぴか時代の人体計測の先駆者であるフレデリック・ウィンスロー・テイラーにも共通するものであった。20世紀初頭、工場の機械化、人工照明、標準化された労働時間によって、労働における人体の生理的限界は、際限のない工業生産性に対する最後の大きな障害であり、解決すべき緊急課題であるかのように思われるようになった。1880年代に始まった有名な時間と動作の研究では、テイラーは労働者の動きを分析し、与えられた仕事を最も効率的にこなす方法を考案した。それは、疲労を減らし、一日の生産量を最大にし、生産コストを極限まで下げるためである。テイラーは、自身の習慣においても、トレードマークである「科学的管理」のシステムにおいても、「自分の力」の生産性を最大限に高めるための鍵として、一貫性、着実性、節制を重視した。そのため、アルコール、タバコ、コーヒーなど、あらゆる種類の刺激物や中毒物は、基本的な生理機能を狂わせ、非効率につながる恐れがあるとして、避けるようにした。

コーヒーは、アトウォーターやテイラーの機械論的な人体概念にはなじまず、相容れない意見や主張によって評判を落としていた。そこで、アメリカにおける労働の科学的研究、労働の定量化に最も責任のある二人が、朝食に最も責任のあるケロッグとポストと一緒になって、コーヒーを不採用にしたのである。

Still, there was one ambiguity at the heart of coffee science that Trigg could not resolve. In refuting Post, he cited multiple laboratory experiments that had concluded that coffee drinking led to an “increased capacity for work.” Yet while the effect was clear, the cause remained obscure: the existing experiments had not definitively established why coffee drinking increased working capacity. As much as he would have liked to clarify the “deplorable” contradictions that had been put forth about the “effects of coffee drinking on the human system,” Trigg could not explain the precise nature of the relationship between coffee, the human body, energy, and work. Though he deferred to Trigg on most scientific questions, William H. Ukers had in the course of his exhaustive research come up with an explanation that seemed right to him. Coffee, Ukers wrote in his foreword, was “a corollary of human energy and human efficiency.” It was “the most grateful lubricant known to the human machine.”

Today caffeine is extraordinary because it is so mundane. Used daily by the great majority of Americans—perhaps 80 percent—it is “by any measure, the world’s most popular drug . . . the only addictive psychoactive substance that has overcome resistance and disapproval around the world to the extent that it is freely available almost everywhere, unregulated, sold without license, offered over the counter in tablet and capsule form, and even added to beverages intended for children.” Yet two centuries ago, at the moment of its discovery, caffeine was anything but mundane. Instead it was a window on nature’s sublime intricacy.

Toward the end of his life, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, the most celebrated intellect in Napoleon’s Europe, could see in his mind the invisible connections that bound the world together. He rejected Descartes’s separation of the mind and the body. He rejected Newton’s idea that the universe could be chopped into free‑standing parts, each of which could be analyzed in isolation from the others. Instead Goethe sought evidence of the wholeness he envisioned, some concrete example of “how the various parts work together.” He told a friend in conversation: “In nature we never see anything isolated, but everything in connection with something else which is before it, beside it, under it, and over it.” His thinking pointed in the direction science was going. German physician Hermann von Helmholtz, who described the conservation of energy in 1847, credited Goethe with anticipating the idea.

In 1819, the seventy‑year‑old Goethe, once an avid coffee drinker, gave to a younger acquaintance whom he thought “quite promising”—a physician named Friedlieb Runge—a box of coffee beans from the port of Mocha and a challenge to figure out what was inside them, how they worked, what they did, what invisible connections they had to the wider world. At the time there was little clarity about the cause and nature of coffee’s effects on the human body: it had confounded centuries of medical thought based on the humoral system, and modern medicine was barely in its infancy—Louis Pasteur, for example, was not even born.

Runge was up to Goethe’s challenge. After a few months of work, he isolated an alkaloid, a plant base, which he called Kaffeine—a compound of the German for “coffee” plus the suffix “ine,” from the Latin for “of the nature of.” For some time, the terms of this discovery were strictly enforced. When an analogous alkaloid was isolated from tea leaves in 1827, it was called “theine,” even after it was shown to be chemically identical to caffeine, which is now thought to have evolved in plants as an insecticide against certain harmful creatures and a stimulant to certain helpful ones. Runge would go on to a successful career in commercial chemistry, among the milestones of which was his pioneering work in synthesizing blue dye from coal tar, permitting textile manufacturers to color their cloth with the by‑products of its fabrication, and forcing indigo producers around the world—including El Salvador—to turn to other cash crops.

The chemical analysis of coffee cast new light on the question of its effects. Coffee was found to contain three “active principles,” or “causes.” In addition to caffeine, there was caffeone, its essential oil, the source of its aroma and flavor, and caffeic acid, its essential acid, which also contributed to the flavor. These findings established a fixed definition of coffee that had important implications for the food business, increasingly concerned with substitutes and purity. Individually, wrote one coffee merchant, “each of these elements possesses virtues or powers of its own, and plays a part in the general effect produced by coffee”; together, these three “active” components gave coffee its “individuality” as an item of commerce. Whatever didn’t have them wasn’t coffee.

Yet even as the definition of “coffee” took shape around these three “active principles,” their action and effects in the human body remained a matter of speculation and disagreement. What exactly did caffeine do, and how? “Coffee acts on the diaphragm and the solar plexus, where it spreads to the brain via immeasurable emanations that escape all analysis,” Honoré de Balzac wrote in 1839. “However, we can presume it is the fluids of the nervous system that conduct the electricity which this substance releases, and which it either finds or stimulates in our bodies.” For many years, the science remained at once definitive and ambiguous. More than a century after Runge’s discovery, one investigator counted more than seven hundred scientific articles on coffee—by “chemists, physiologists, psychologists, dietitians, physicians and food inspectors, in fact from every type of scientist who has anything at all to do with the preparation, analysis or effect of foods and articles of diet.” Two hundred thirty‑two of these, fully a third, focused on the question of coffee’s effects on the body. Their findings, as Charles W. Trigg lamented, were often wildly at odds with each other.

Even in W. O. Atwater’s calorimeter, where the operation of the human body was measured with unprecedented precision, coffee’s effects were obscure. Though German studies of workers’ diets had previously tried to account for coffee’s contributions to labor power, Atwater set coffee and tea apart from other foods, delinking caffeine’s effects in the body from the small number of calories—derived from the fat, or essential oil—in a cup of coffee. In studies of the food necessary “to live a day of the life of an ordinary man, say a mechanic or day‑laborer, doing a fair amount of manual work,” Atwater acknowledged that many subjects were drinking coffee regularly, but he left it out of his final energy accounting in an effort to “simplify the calculation.”

“Tea and coffee,” he wrote, “are not foods in the sense in which we use the word”— “material which, when taken into the body, serves to either form tissue or yield energy, or both.” He knew coffee was doing something to the body, and to respiration and metabolism specifically—“it has an invigorating effect, and may at times aid digestion”—but he could not make sense of these effects in terms of calories, so it seemed dubious. “Perhaps most of us would be better off if we did not drink tea or coffee,” Atwater concluded, and kept to the principle in his laboratory. While W. Smith was in the calorimeter, laboring over German treatises on physics to understand the laws his body could not help following, he had only water and milk to drink.

Atwater’s reservations about coffee were shared by the other pioneering Gilded Age inspector of the human body at work, Frederick Winslow Taylor. In the decades around the turn of the twentieth century, factory mechanization, artificial lighting, and standardized clock time made the physiological limits of the human body at work look like the last great obstacle to unbounded industrial productivity, and an urgent problem to be solved. In famous time and motion studies begun in the 1880s, Taylor analyzed workers’ movements to engineer the most efficient way of performing a given job, in the interest of reducing fatigue, maximizing output each workday, and paring the costs of production down to a hard minimum. In his personal habits and his trademark system of “scientific management” alike, Taylor emphasized consistency, steadiness, and sobriety as the keys to maximizing the productive use of “one’s forces.” As a result, he avoided stimulants and intoxicants of all kinds, including alcohol, tobacco, and coffee, for fear that they would throw off basic physiological functioning and lead to inefficiency.

Its reputation clouded by conflicting opinions and claims, coffee did not fit neatly into Atwater’s and Taylor’s mechanistic concepts of the human body. So the two people most responsible for the scientific study of work and quantification of labor in the United States joined Kellogg and Post, the two people most responsible for breakfast, in disapproval of coffee.

Augustine Sedgewick(2020)"Coffeeland: A History" 16. The Truth about Coffee

コーヒーの核心が「人間の機械にとって最もありがたい潤滑油」であるという比喩は必然的に、コーヒーを近代人の生活の中心を担う「労働」に結び付ける。しかし、我々はコーヒーを含む嗜好品を労働のくびきから解放し、今一度文学の対象としなければならない。嗜好品は欲望の対象であり、その意味は歴史的・社会的な文脈で決定される。この欲望は、生理的欲求に対しては二次的なものであり、それ自体への指向というよりも、その必然的帰結(副産物)への期待である。そのため、嗜好品の本質は決して触れることのできないものとして残る。嗜好品の「活性原理」は我々を饒舌にし、触れえぬものを巡って我々を永遠に語らしめるのだから。